Chapter-by-Chapter Summaries

[edit]

Chapter 1

Outlines the general approach. Uses survey data from 1948, 1952, and 1956 (not much from 1948).

[edit]

Chapter 2

Chapter 2 details the "funnel analogy," the central argument in this book. The funnel works like this:

Political socialization (mainly your parents' party identification) determines party ID, which determines your political attitudes, which determines how you actually vote.

Party ID is seen as an "enduring psychological attachment." The political attitudes it determines are measured along six dimensions:

1.How you feel about the Democratic candidate

2.How you feel about the Republican candidate

3.How well each party manages the affairs of government

4.Group interests ("he represents business owners" or "little people": people like me vote for so-and-so).

5.Domestic policy issues

6.Foreign policy issues

[edit]

Chapter 3: What our attitudes are

•Generalization: Our attitudes (both cognitive and affective) bleed over from one thing to another. In particular, our attitudes about a party affect our attitudes about a candidate.

•Threshold of awareness: It takes a lot for the masses to take note of something. Although Stevenson had a clear, frequently stated position on foreign policy issues, most people didn't know them. They pay far more attention to you once you're president than they do to you as a candidate.

•Social bases of stability: Some perceptions are stable, others fleeting. This can depend on several factors. For example, it took two decades for citizens to forgive Republicans for causing the Depression and give another Republican a chance. But other perceptions seem to fade much more quickly.

[edit]

Chapter 4: How our attitudes affect our voting behavior

•See pg 74 (note 7): you can predict voting behavior well based on attitudes about the candidates. Predictions improve by including attitudes about domestic and partisan issues.

•See figures starting on pg 82. The authors asked five questions on which people could take a partisan position (or not). Some people took a partisan stand on all five, some on fewer. Some had consistently Republican/Democratic stands, others did not. Based on number and coherence of stands, you can predict party-line voting, passion about the election, how early the respondent will make a decision about who to vote for, etc. [See Zaller and Feldman 1992.]

[edit]

Chapter 6: Partisanship

•Vote Choice is the sum of a field of forces.

•Partisanship is an antecedent to those forces.

•As shown on p 137, partisanship correlates well with voting but does not explain all of the vote choice.

•Strong party identifiers tend to be more interested in politics.

•Even Democrats have generally Republican attitudes about foreign policy, and even Republicans have generally Democratic attitudes about domestic policy (see p 129-130).

[edit]

Chapter 7: Origins of partisanship

•Early socialization (family influences)

•Partisanship is stable over time

•Youth lean Democrat

•Minorities lean Democrat (Catholics, Jews, blacks); perhaps they are drawn to Democratic ideas of social equality.

[edit]

Chapter 8: Public policy and political preference

Before an issue affects your vote, three things must happen:

1.You must be aware of and know something about the issue. (It must be "cognized.")

2.You must care about it, at least minimally. (Operationalized: You must have an opinion about a specific piece of legislation. E.g. pg 172: Are you in favor of or opposed to the Taft-Hartley Act?)

3.You must know what the parties say about the issue (does your party support or oppose Taft-Hartley).

Basically, this chapter requires you to know a LOT about an issue in order for it to affect your vote. You need to know which laws deal with it and so on. Really, the only laws anybody has heard of in the past five years are the Patriot Act and No Child Left Behind. But not only do you need to know the name of the bill--you also need to know the details (not just the subject) of the bill.

[edit]

Chapter 9

Familiarity with politics varies; some people know a good bit about several issues, some know very little about any issues. However, individuals do tend to have a firm sense of how the parties differ. This, combined with an assumption that voters have stable underlying values, would explain why voters tend to stick with a single political party.

Some individuals form their views on individual issues from an underlying set of general principles, however small it may be. Many, though, simply take each new thing as it comes, with little overriding ideology. We should not assume that an individual has a coherent ideology simply because his views are congruent, though.

Attitudes about foreign and domestic policy tend not to correlate (positively or negatively). One who favors domestic interventionism does not necessarily favor foreign interventionism as well. "Internationalist" ideals also do not correlate with membership in either party, despite the parties' reputations. However, "interventionist" (domestically) ideals do correlate with membership in the Democratic party.

Many people have "non-scalar" opinions (they don't appear to have congruent views). However, non-scalar patterns occur in both parties (though they are least frequent among strong partisans, not independents).

Ideological sorting does occur: those who have "liberal" views tend identify more strongly with Democrats. However, this doesn't mean that they are ideological. Instead, people seem to concern themselves with "primitive self-interest." Only some people appear to be ideological: low-status Republicans and high-status Democrats. (Wealthy Republicans and poor Democrats, on the other hand, are just sorting according to class, not ideology).

[edit]

Chapter 10

Frequently, analysts assume that most voters are (1) sensistive to their policy position on a left-right continuum and (2) sensitive to both parties' shifting positions along that continuum (pg 217). Thus, they speak of the results of an election as indicating an ideological shift in the electorate or by one of the parties. However, only a minority of the electorate actually meet these two conditions. This ideological behavior is only one of several "frames of reference."

The "frames of references" (analogous to Converse's (1964) "levels of conceptualization"):

[edit]

Level A: Ideology and Near-Ideology

An abstract level of thinking about politics: what is good and bad (principles). You don't have to use the correct intellectual terms, but you need to be forming your opinions about specific issues in relation to broader, more abstract notions.

Comment: In reality, all the examples they provide of "ideologue" interviews seem to differ from the "group benefits" interviews in only one respect: the "ideologues" used the words "liberal" or "conservative" to describe the parties, while the "group benefits" people spoke about issues. This seems to be a strange criterion to use in sorting people into levels of political sophistication. All we really learn is that only around 6 percent of people use the words "liberal" and "conservative" when speaking about the parties.

[edit]

Level B: Group Benefits

A more concrete way of thinking about politics; "ideology by proxy." We view candidates or parties as friendly or hostile to people like us (our group). We worry little about "long-range plans for social betterment" (234), and instead think about whether a party/candidate is "for" my group: farmers, the working class, the poor, etc.

[edit]

Level C: The "Goodness" and the "Badness" of the Times

Unlike Level D, these people do make some reference, "however nebulous or fragmentary," to some public policy issue (240). And unlike Level B, these people don't really perceive group interests. They form opinions based on whether times are good. The incumbents are doing well if my family is doing well. The incumbents are doing poorly if the war is hurting our country.

[edit]

Level D: Absence of Issue Content

Although these people fail to comment on anything related to a current political debate, they made up 17 percent of the voters sampled in 1956. They tend to overlook the policy differences between the parties and worry instead about the candidates' personal characteristics ("their popularity, their sincerity, their religious practices, or home life", pg 244).

•Example: One interviewee, when asked what she likes about the Democrats, responds only, "I'm a Democrat, that's all I know" (p 247). What do you like about Stevenson? "Stevenson is a good Democrat."

· · · · · · (

收起)

An Economic Theory of Democracy pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

An Economic Theory of Democracy pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Designing Social Inquiry pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Designing Social Inquiry pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Coercion, Capital and European States, A.D.990-1990 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Coercion, Capital and European States, A.D.990-1990 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Rethinking Social Inquiry pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Rethinking Social Inquiry pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Voting for Autocracy pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Voting for Autocracy pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Passion, Craft, and Method in Comparative Politics pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Passion, Craft, and Method in Comparative Politics pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 商業與聯盟 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

商業與聯盟 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Case Study Research pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Case Study Research pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Democracy and Development pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Democracy and Development pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 特朗普評傳 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

特朗普評傳 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 A Very Stable Genius pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

A Very Stable Genius pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 拯救美國 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

拯救美國 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Our Divided Political Heart pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Our Divided Political Heart pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 American Grace pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

American Grace pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Basic Interests pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Basic Interests pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 The Making of the President 1960 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

The Making of the President 1960 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 權力遊戲 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

權力遊戲 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Red State, Blue State, Rich State, Poor State pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Red State, Blue State, Rich State, Poor State pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Identity Crisis pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Identity Crisis pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 The Making of Donald Trump pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

The Making of Donald Trump pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 二戰後的美國對外政策 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

二戰後的美國對外政策 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 17歲,我在美國當“政客” pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

17歲,我在美國當“政客” pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Why Is There No Labor Party in the United States? pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Why Is There No Labor Party in the United States? pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 The Accidental Superpower pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

The Accidental Superpower pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Presidential Party Building pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Presidential Party Building pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 Congress pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

Congress pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 我在最高法院的日子 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

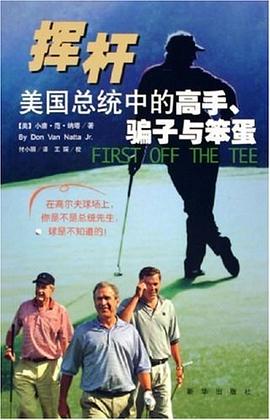

我在最高法院的日子 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載 揮杆 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載

揮杆 pdf epub mobi txt 電子書 下載